The following essay/meditation is from my sister project, Pneuma. If you’re interested in this essay and would like to listen to the podcast, visit the website pneumameditations.com or search Pneuma By Daniel Finneran on any of your favorite podcast streaming platforms

Hello friends, and welcome to another episode of Pneuma

A few episodes back, I introduced to you a concept by which I’ve always been entranced, and to which, because of its (continual) charm, I can’t help returning again and again: Eudaimonia.

Eudaimonia.

According to its narrowest definition, which comes to us from Greek, it means “good spirit”, but, through the passage of time, it’s been extended to mean everything from “happiness”, to “wellbeing”, to “contentment”, to an overall “good life”.

A good life.

Ah yes!–a good life. A life marked by a sound spirit; a just conscience; an even balance; a virtuous soul; a tranquil mind; a placid contentment; a quiet satisfaction; a love of nature; a reverence for the transcendent; an affection for friends; a confidence in oneself; an inner peace–is this not the state of being of which we’re all in pursuit, for whose attainment we’d spend any amount of money, endure any hardship, and suffer any toil?

I think that it is. I think this universally to be the case.

You see, in our pursuit of the good life, we join the company of all mankind–a company to whose ancient “hunting party”, we are but late arrivals.

Happiness–its acquisition is the consuming interest of us all, not just the living, but the dead, and not just the dead, but those yet unborn. Those who sought it most earnestly, into whose grasp it didn’t so easily fall, include the greatest philosophers who have ever lived–men like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Epicurus.

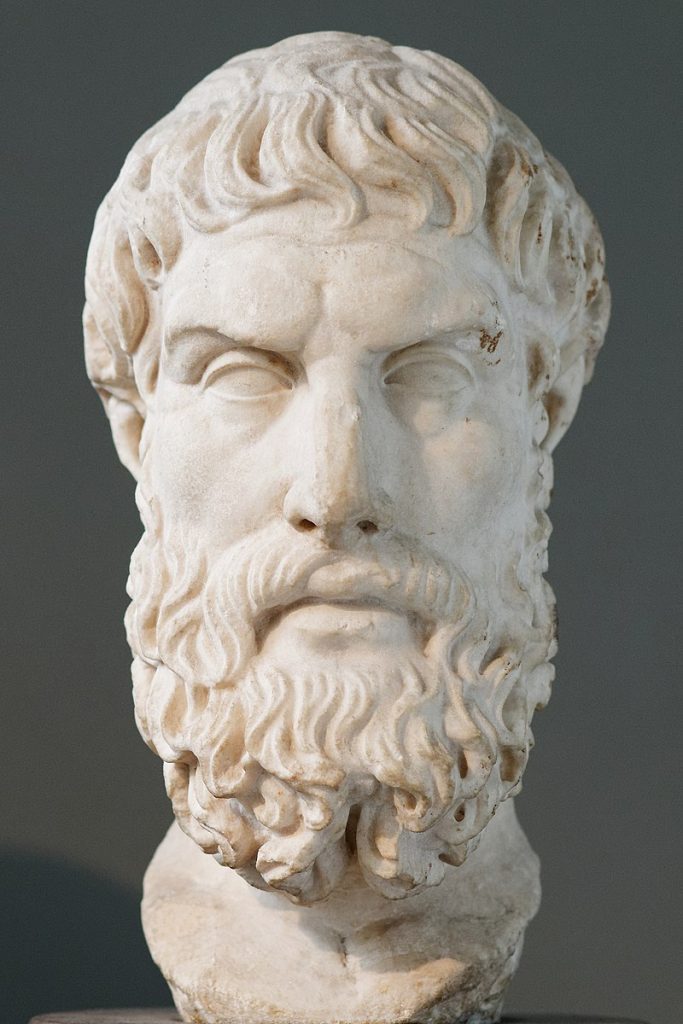

Epicurus, it should be said, was no epicure. Not in the modern sense, at least.

Born on the island of Samos just off the Turkish coast, he settled on the outskirts of Athens at the age of thirty-four. There, in that renowned city of oratory and learning, he opened the gates to his eponymous garden, in which, despite the disapproving glares cast by his neighboring farmers, few crops were ever grown, but out of which, for the future nourishment of all mankind, a flourishing school based on his precepts sprang.

And what were his precepts?

What was Epicureanism, rightly understood?

For one, it was atomistic, upholding Democritus’ view that there are unchanging, indivisible particles called atoms. Aside from them, there is infinite space, also called the “void”, through which the atoms move.

For another, it was materialistic, rejecting the Platonic idea that there are higher, undetectable, supra-sensory things. All things, in this view, are matter–nothing more.

Finally, it was eudaimonic. Its ethics was aimed at achieving happiness, contentment, peace–the components of a “good life”.

And precisely how, according to the Epicurean doctrine, was the good life to be achieved?

Is there a script that we, two-thousand years and as many miles removed from him and his garden, can follow?

In Epicurus’ letter to Menoeceus, one of his three extant epistles and, from an ethical standpoint, the most important, the philosopher of pleasure spells it all out.

First, it’s not the longest, but the richest and best life after which one should aspire.

If our palates are refined, and our appetites well-governed, do we not treat food in the same way?

As Epicurus advises, “We should prefer the most savory dish to merely the larger portion”.

Ruth’s Chris v. Golden Corral; Capital Grille v. Pizza Hut: It’s rather quality than quantity that concerns us.

The same is applicable to time, to whose prolonged, bland duration, little value is attached, if it be not flavored and seasoned with the full zest of life.

The Good life, then, prefers not a long and dull, but a short and sweet experience.

The twin goals of happy living, Epicurus says, are “bodily health and imperturbability of mind”, the latter being perhaps the more important.

To achieve these twin goals, we must enjoy “freedom from pain and freedom from fear”–that which afflicts, respectively, the body and the mind. Note, these are not positive, but negative freedoms. They are freedoms from, not freedoms to, which would be positive.

We must live simply.

We must monitor our desires and limit our appetites (no small task, now that Ruth’s Chris is on my mind!)

The limitation of the appetites is, in Epicurus’ mind, “a major good”.

“Those”, he says, “who need expensive fare least are the ones who relish it most” when, on occasion, they have the opportunity to try it.

They consume it; it doesn’t consume them.

They can taste it, appreciate it, step away from it, and return, without disturbance, to the simple, austere table whence they came.

Thus, the diet most conducive to a “good” life is the simplest.

“Plain foods”, Epicurus says, “afford pleasure equivalent to that of a sumptuous diet”.

If you eat mindfully, fast intermittently, focus on nutritional density, and season all your meals with hunger (the seasoning than which no spice, not even cayenne pepper, is stronger!) you will be on your way toward a Good life.

In Epicurus’ words, “Becoming habituated to a simple rather than a lavish way of life provides us with the full complement of health”.

It should be said, the Good life, whose defining feature is the absence of bodily pain and mental anguish, is not to be found in low pleasures.

“The pleasant life”, Epicurus warns, “is not the produce of one drinking party after another, or of sexual intercourse with multiple partners, or of expensive food and other delicacies afforded by a luxurious table…”

“On the contrary–it is the result of sober thinking”.

“Plain living and high thinking”, as the poet William Wordsworth says. He, a Romantic many years displaced from the agora of fourth-century Athens, encapsulates the Epicurean way.

The Good life, you see, is a life of the mind.

The Good life is a thoughtful life.

The Good life is a meditative life.

It’s a life for which all of you, my brilliant Epicurean listeners, are perfectly fit and naturally suited.

Plain living and high thinking.

You need not seek more.

That is the true path to Eudaimonia–to the Good life that awaits.

Plain living and high thinking.

That is the Epicurean way.

Thank you so much for spending some time with me and listening to this episode. If you found it useful, delightful, pleasurable, don’t hesitate: subscribe to this channel and share it with friends. Stamp it with a five-star rating and urge them to do the same.

My website, pneumameditations.com, on which I’ll be posting articles and transcripts, will soon be up and running. In the meantime, take a peek at my sister podcast, Finneran’s Wake, on which more philosophical matters are covered.

Until next time, farewell, from Pneuma