There are, for better or worse, two things with which Key West is synonymous: one is “Fantasy Fest”, the annual ten-day bacchanal at the end of October to which thousands of topless revelers flock.

The other is Ernest Hemingway.

With the exception of the striped concrete buoy that marks the island’s “Southernmost Point” , no place on Key West attracts more visitors than the famed “Hemingway Home”. A breezy, shaded, quaint, two-story Bahamian-style house, the “Hemingway Home” is, by any measure, a beautiful place. It’s an historic structure. Indeed, it’s a story in itself. And thus, since 1964, it’s existed as a museum open to the public, through which I had the good fortune to take a tour this past June.

While it was a deeply moving experience for me, not everyone feels the same.

To many, the house is little more than a welcome respite from the hot tropical sun (merciless that time of year!). It is, in the opinion of the profusely sweaty, as convenient a place as any for a moment’s refuge from the oppressive heat. To others, it’s a fun, scenic, “Instagrammable” background against which to snap a fetching selfie (I think I inadvertently “photo-bombed” more than a few). Still to others, it’s a popular spot to which Google suggests they go before embarking on the evening’s daiquiri-fueled pub crawl.

To me, an unwaveringly sober traveler, it was something different.

It was a pilgrimage, of sorts.

It was a sacred journey.

It was a visit to a hallowed place in which an iconic man, an American legend, a literary genius once worked and lived.

The eponymous yellow mansion in which Hemingway resided for almost a decade still has a certain magic about it. It’s palpable. Unseen, but strongly felt. Although I can provide no proof of the assertion, if you ask me, I think it’s haunted. That’s right: haunted. But not in a bad way. Inhabited not by a ghoulish specter intent on terrorizing those who pay their twenty dollars, inhale the conditioned air, and mosey along their idle way, but by an affable ghost. A friendly spirit with whom we’re meant to share a laugh, a smoke, a barb, perhaps a glass (or an entire bottle!) of delicious rum, and–unreservedly, and for many hours–to commune.

You need only feel the unseen, and open yourself to the possibility of life beyond the grave. To life beyond the deep. To life out on the open sea, atop a range of snow-capped mountains, on the banks of a fathomless lake, or in the depths of an impenetrable jungle. If you do, right there in the famed Hemingway Home on tiny Key West, you might just be able to converse with the immortal man, “Papa” Hemingway, the Father of Modernism and America’s greatest literary icon.

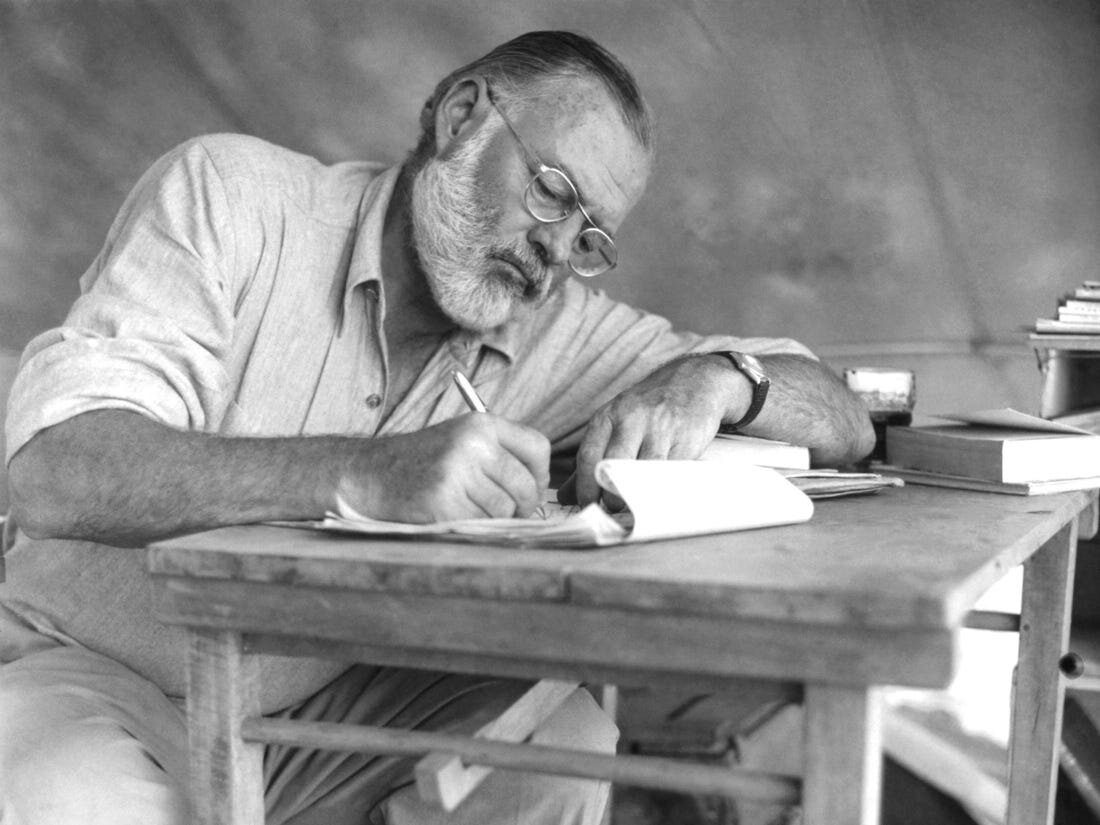

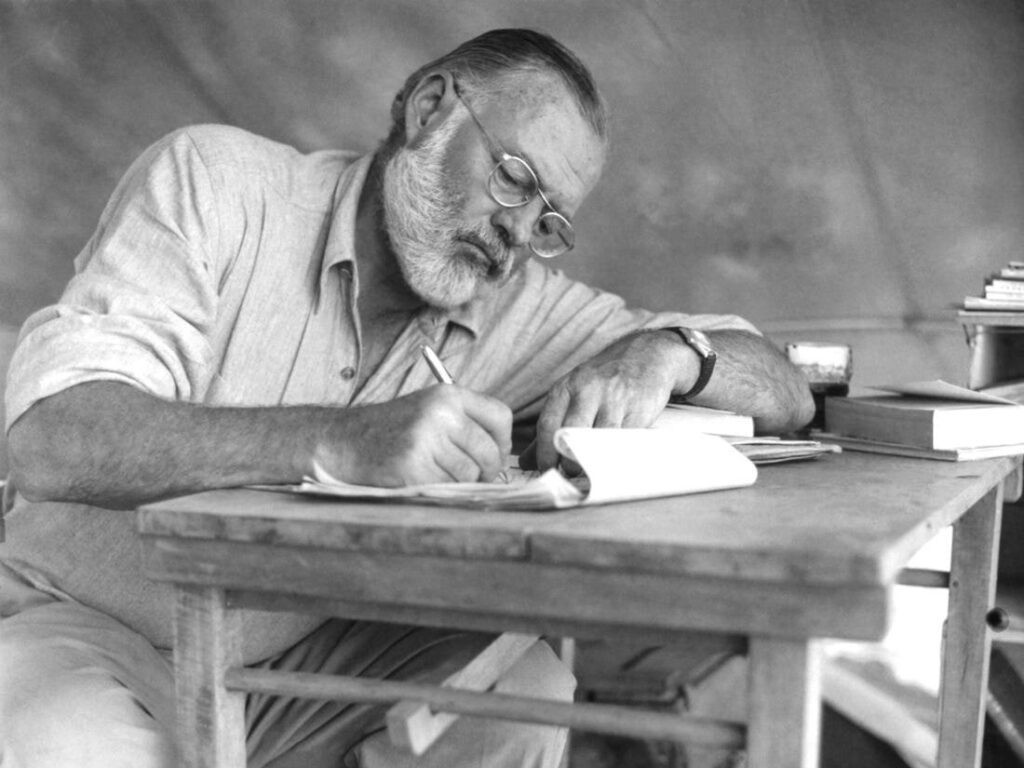

In the often-strained company of his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, Ernest Hemingway lived in this house between the years 1931 and 1939. This decade was one of the most prolific of his literary career. During this stretch of time, he wrote Death in the Afternoon, Green Hills of Africa, a slew of articles, diary entries galore, and, his longest work, For Whom the Bell Tolls. In the detached guest house overlooking his wife’s pool, Hemingway would settle down each and every morning (early, no later than six AM) and commit himself for the next five hours to his passion and his craft.

(It should be noted that it wasn’t until noon that he began drinking, fishing, boxing, womanizing, and living–temperance being a virtue best confined to the morning hours!)

As I stood in the cramped doorway of that historic room, through which a languid train of six-toed cats casually sauntered, I felt the presence of Papa Hemingway’s spirit.

I visualized, seated right there before me, hunched over a typewriter in the midst of mounted deer and fish, the mythical man. There he is: beard in full bloom, fountain pen in hand, and an inextinguishable flicker of genius in his eye. His tan, youthful skin, preserved by the Caribbean sun, makes for a dark canvas against which his bright smile shines. Can you not see him? Close your eyes! Is he not there before you? Shall we imagine him together?

There he is, in the sublime poise of that beautiful house, in a state of incessant movement. Movement? Yes!–movement! Movement in the mind, that is, in which thoughts will never sit still. As he’s seated, as he types, he’s transported back to the decadent streets of France, the bullfighting rings of Spain, the hunting grounds of Africa, and the dangerous fighting fields of Northern Italy in which, as a volunteer ambulance driver during WWI, he was gravely injured.

While I stood there, I began to reflect on my first experience with Hemingway.

I was a junior in high school, no more than seventeen years of age, when I was assigned to read his critically-acclaimed book, The Old Man and the Sea. This slim book, to which the 1953 Pulitzer Prize was awarded, was my introduction to Hemingway. And what a memorable introduction it was! And as I stepped into his writing room there in Key West, I was suddenly transported back to my childhood home in the quiet suburbs of New Jersey, where first the author and I met.

Upon my return home from Key West, I scanned my overstuffed bookshelf for my old Hemingway collection. There it is! Deep in the corner, flanked by CS Lewis on one side, and Edward Gibbon on the other (strange but good company, I think). Like a timid snowfall at the start of a long winter, a light coat of dust had settled upon its case and the four volumes it housed. A pinch of guilt squeezed me as I approached the case and wiped away the thin film to which the years had quietly added their layers.

There! Good as new!

I proceeded to open these cherished books from my youth, from that carefree state of innocence to which life prohibits our return, and to read them again. Now, I read them closely. Indeed, I read them through the eyes of a man who is chronologically (if not always emotionally) more mature than that boyish seventeen-year-old from Sewell.

In so doing, one necessarily accepts a risk: once viewed more critically, a book will usually lose some of its original power. It will bleed some of its original vigor. It will lose some of the glorious luster with which the eye was dazzled. It’s hard to avoid. The force with which a book gripped you as a child will, almost inevitably through the passage of time, be weakened. The original impact will be blunted. Worse, you’ll think yourself silly and unsophisticated for having thought highly of a work upon which educated people bestow few plaudits.

Or, alternatively, your re-reading is a transcendent experience that confirms you of all your earlier beliefs.

What follows, then, is a brief review and criticism of Hemingway’s best-known works, put forward by a man who has, all of a sudden, grown somewhat old.

THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA

With what other book would I begin than that to which I was, at the tender age of seventeen, first introduced?

The Old Man and The Sea, published in 1952, was Hemingway’s final book. As previously noted, it received the Pulitzer Prize just one year later. Upon its publication, it was deemed, by critical and lay readers alike, an instant classic. Commercially, it was a boon; Life magazine secured a bid for its distribution. Normally, such works would be published seriatim, perhaps over the course of many weeks, so as to avoid taxing the reader and (more importantly) to ensure he’d return to the newsstand and purchase himself the newest copy.

But Life opted to print the entire novella in a single issue. It was a good decision; in just two days, Life sold about 5.3 million copies, a record yet unsurpassed by anything the magazine has put out.

While the readership of Life has since declined, the reach of Hemingway’s final work has only grown. To this day, The Old Man and the Sea remains a huge success. In brick-and-mortar bookstores and all across the web, many thousands of copies are sold annually. It was the last novel that Hemingway wrote, the first with which numberless students are acquainted and, for those two reasons, the work with which he’s most often associated.

For a variety of reasons (least of all the beauty of its prose) The Old Man and The Sea is an ideal book for a teenage student beginning his journey into American literature.

For one, it’s short, and thus congenial to the vanishingly small attention span of people that age. Its 127 pages can be read in a single day. They certainly demand no longer than a weekend for their completion. Second, there are only a few characters to remember (three if you count non-human characters): Santiago, the titular “old man”; Manolin, an industrious boy with whom old Santiago is good friends and occasionally works, and the marlin. Third, there’s enough action to attract and hold the interest of a young reader who’s been brought up on Fortnite and Grand Theft Auto. Deep sea fishing, a marlin leaping, harpoons whizzing, sharks attacking–scenes from which the attention isn’t easily diverted. And, fourth, the symbolism, while not in the least subtle, is a good way to get young readers thinking metaphorically.

For that’s what The Old Man and The Sea really is: an extended metaphor about life and death, God and man.

Extended, but unsubtle, and that, I think, is the book’s biggest weakness. The allegory is too strained. It’s too cumbrous. It obtrudes too much and too often. Time and again, like a wild marlin’s flapping tail, it leaps out from the page and slaps you over the head. Whack! Good, perhaps, for the undiscerning reader of seventeen whose head requires an occasional knock or two, but not so good for the reader whose mind is a bit more sensitive to things blunt and obvious.

Santiago is, as every high school English teacher is quick to inform you, a literary Christ figure. For my money, I think he’s one of the finest examples of the trope. At least twice in the story, Santiago bears and carries his mast (read, his cross) on his hunched and wearied back. As he does, one can almost picture the Son of God trudging along the harrowing road to Golgotha. From his ceaseless toil, Santiago’s tired hands are marred, disfigured, and bloodied–an injury reminiscent of Christ’s stigmata. He suffers much, but complains little. From the outset, his fate appears to be preordained. Like a stoic, though, he endures his wretched lot until the very end. Despite every adversity, in defiance of every hardship, he simply refuses to be cowed.

He won’t give in.

“A man”, he declares with unflinching resolution, “can be destroyed but not defeated”.

Is that not, in a single sentence, the entire lesson of the risen Christ?

FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS

For Whom the Bell Tolls, published in 1940, borrows its title from a John Donne poem. The original poem, written in 1623, is a touching meditation on the interconnectedness between you, me, and every single member of our species. It speaks to the universal brother and sisterhood into which we’re all born–a union from which not even the most unsociable brute can exempt himself. In our current age of atomization, during which the bonds of community and friendship have all but dissolved, I think it’s a poem that very urgently merits our recitation.

As an aside, one thing that can be said uncontroversially about Hemingway is that he possessed an infallible skill at choosing great titles for his works. Just take a moment and recite aloud the following titles of his oeuvre:

For Whom The Bell Tolls

The Old Man And The Sea

A Farewell To Arms

The Sun Also Rises

Clean, short, monosyllabic, and yet so vigorous! There’s power in the concision, packed tightly with the expectation that, at any second, its contents might explode. The matter is small, but fissile. Each title is simple, yes, but absolutely pregnant with meaning. Each is lapidary to the extreme, as though carved by a hand unbound by time or place. There’s a certain music to them, I think, whose thumping rhythm and forward momentum is echoed in Hemingway’s prose.

Whereas A Farewell to Arms is set in northern Italy at the close of WWI, For Whom the Bell Tolls takes place in the middle of Spain during the country’s bloody three year civil war.

Unlike the former war, of which Hemingway partook, the author was not directly involved in the Spanish Civil War. He was, rather, deployed there on assignment as a reporter for the Toronto Sun.

It’s interesting to contrast Hemingway’s fictionalized account of the war to the unromantic first-hand report offered by George Orwell, a contemporary and fellow novelist whose Homage to Catalonia is considered by many to be the expat mercenary’s locus classicus. Orwell, then widely known by his Christian name, Eric Blair, served valiantly in a regiment under the POUM (the Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, or the “Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification”. To think!–the author of Animal Farm fought for the side bankrolled by Napoleon-Stalin!). Like Hemingway in WWI, Orwell suffered an incapacitating wound (an early-morning sniper’s bullet to the neck) that forced him to retire from the field of action.

As mentioned, Hemingway wrote For Whom The Bell Tolls while living in Key West in the late 1930s. The book was published in the autumn of 1940, not quite eighteen months after the end of the Spanish Civil War. Hemingway’s reputation, by that time, was firmly established; no longer young enough to be a prodigy, he was considered by many critics to be the generation’s most talented writer. He was said to give “voice” to the “Lost Generation”, those who came of age in the wake of WWI. The Spanish Civil War was still fresh on everyone’s mind (Hitler hadn’t yet annexed Poland) and Hemingway was just the man to romanticize its carnage.

If I were asked to summarize For Whom The Bell Tolls in the author’s characteristically laconic style, I would respond thus:

“An American professor with an aptitude for dynamite, and a fluency in Spanish, leads a brigade, falls in love, blows up a bridge, and fractures his leg”.

And possibly dies.

The end.

Robert Jordan (known, not altogether affectionately, as Roberto the Ingles) is an American professor at the state university of Montana. His speciality is Spanish, but he’s also proficient in the use of explosives. He spends his summers working as a road engineer in Spain. It just so happens that the intersection of these two skills make him an invaluable asset to the Republican guerrilla unit for which he’s volunteered to fight. Despite the highly charged, ideological nature of the war, Robert Jordan is not, at this point, an overtly political creature (“What were his politics then? He had none…”) and we’re never informed of his motivations for joining this ragtag Marxist militia.

And yet, despite our ignorance of his motivations and his political allegiance, we’re captivated by his every move. He’s a true hero, right up till the end. As he pursues, with unflagging courage, his singular goal to blow up the bridge, we can do little else but jump onto his bandwagon and hope for his success.

Three scenes, in my opinion, stand above all others in their vividness, power, and importance: that in which Pilar, the group’s strong-willed, foul-mouthed leader, recounts the bloody execution of the fascists in her town; that in which Robert Jordan and Maria, his nineteen-year-old Spanish girlfriend, make love for the first time in the soft grass; and that in which Robert Jordan, after overcoming numerous setbacks and the treachery of Pablo, detonates the explosives, collapses the bridge, breaks his leg, and prepares to die.

Interspersed between these three gripping scenes are profound meditations on life, love, religion, war, and death.

I’ll share just a few memorable quotations that touch upon these themes:

“I think that after the war there will have to be some great penance done for the killing. If we no longer have religion after the war, then I think there must be some form of civic penance organized that all may be cleansed from the killing or else we will never have a true and human basis for living”.

Such is the dehumanizing effect of slaughtering, en masse, our fellow man. And what, exactly, is “penance” in a post-Christian world? Modernists like Hemingway were forced to confront this question. It undoubtedly plagued him.

“The things he had come to know in this war were not so simple”.

The commission of gruesome and unpardonable war crimes on the part of the “good” Republicans, of which Pilar gives us a few nightmarish examples, would certainly lead one to this sobering conclusion. In war–be it the current Russo-Ukraine War, the Vietnam War, or the Peloponnesian War–acts of dubious morality are committed by “good” and “bad” alike.

“How little we know of what there is to know. I wish that I were going to live a long time instead of going to die today because I have learned much about life in these four days; more, I think, than in all the other time. I’d like to be an old man and to really know. I wonder if you keep on learning or if there is only a certain amount each man can understand. I thought I knew about so many things that I know nothing of. I wish there was more time”.

No commentary from me, dear reader, can elucidate what the author says so well.

While it’s Hemingway’s longest book, we mustn’t forget that the action in For Whom The Bell Tolls is confined to four brief days. From start to finish, not quite one hundred hours go by. In that regard, relative to the next two books we’ll examine, it’s very brief (the events in The Old Man And The Sea, in contrast, take place over the course of a single day). The briskness and urgency of these four days is interrupted by stories and metacognitive digressions that extend it, perhaps unnecessarily, to four hundred and seventy-one pages.

A symbol oft-repeated to which you should be alert–if, by some chance, it manages to escape your notice–is the “movement” of the earth. The tremors of the earth are caused not only by physical, but by spiritual and romantic forces. When the bombs are finally detonated, the earth is tossed way up in the air. Rocks, roots, shrubs, dirt, and small trees are thrown every which way. The ground quakes in every direction as the soil is upturned and the bridge falls down. That is the physical movement of the earth.

When Robert Jordan and Maria make love in the grass, they describe feeling as though the earth below them shook (“Did thee feel the earth move?”, Robert asks Maria, to which she responds affirmatively). They mean this not merely metaphorically; they really think that the plates beneath them shifted. It was a tectonic event, surely measurable by the Richter Scale. They really think that the world quivered.

And so it may have.

But not for me.

It pains me to say this, but For Whom The Bell Tolls doesn’t quite shake my soul as it did those of the ill-starred lovers. It doesn’t cause me to tremble. If it does happen to move me in any serious way, it is in lulling me half to sleep! With the exception of a few passages that are exciting and very nicely written, the prose is, overall, flat and stilted. Yes–stilted; that seems to be the word that every critic agrees upon and applies to the book. They do so because it’s applicable. The stiffness of the prose is, they say, a consequence of Hemingway’s attempt to translate Spanish into English directly. It results in, as one critic describes it, a “medievalism” that grates on modern ears.

While it’s a bold and an ingenious attempt, ultimately, it can’t be declared a success. At least not by this reviewer. The book ends magnificently, but it’s a tedious path to get there–regardless of whether you travel over bridges or not.

THE SUN ALSO RISES

The Sun Also Rises, published in 1926, was Hemingway’s maiden work. Not yet thirty years of age–and thus devoid of the deep well of creative ideas, experiences, and symbols from which he’d later draw–it should come as no surprise that the book is largely autobiographical. Indeed, it’s almost entirely autobiographical, with only a thin facade of fiction laid atop the reality through which he lived. It is, to borrow a useful term from French, a roman à clef, or a “novel with a key”. In such a work, the real people, places, and events that the author interacted with are cleverly disguised. The “key”, inaccessible to all but the members of an inner-circle, is that which unlocks and connects the fictitious to the real.

The title comes from a passage in Ecclesiastes:

“One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh; but the earth abideth forever…the sun also riseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to the place where he arose…the wind goeth toward the south, and turneth about unto the north; it whirleth about continually, and the wind returneth again according to his circuits…all the rivers run into the sea; yet the sea is not full; unto the palace from whence the rivers come, thither they return again”.

This arresting passage is a mere two lines removed from the immortal, eminently quotable declaration with which Ecclesiastes begins: Vanitas vanitatum, omnia est vanitas (in English, “Vanity of vanities! All is vanity”). With the formidable exception(s) of “Let there be light!”, “Am I my brother’s keeper?”, and “Let my people go!”, I can think of no other line in the Bible that is more universally known and oft-repeated.

Interesting to note is that Hemingway, at this formative stage of his life, was undergoing a conversion to Catholicism. No doubt, he was raised a Christian, but, throughout his childhood in Illinois and his young adulthood abroad, he was never especially devout. While living in Europe, he’d become a habitual reader of the King James Bible, of whose beautiful Old Testament writings he was particularly enamored. Indeed, one can readily discern the influence of the old Hebrew prophets on his prosody; its rhythm, restraint, power, crispness, and beauty are an echo of their sacred music.

Mix with that a touch of Mark Twain and a sprinkling of Walt Whitman, and a little advice from Ezra Pound to forgo the use of adjectives, and you have, in essence, the style of Ernest Hemingway.

That memorable passage from Ecclesiates is one half of the epigraphs that introduce the novel. The other comes from Gertrude Stein, Hemingway’s friend, confidante, and fellow expatriate. In 1903, Stein emigrated from America and settled in France, where she established a popular salon and lived for the next four decades. In conversation, Hemingway quotes her as having said:

“You are all a lost generation”.

And so they were.

And it’s the purpose of The Sun Also Rises to tell their tale.

The book is divided into three parts: the first and last third are relatively brief. It is in the second that all the vigor and momentum of the story resides. The book opens rather abruptly; F. Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway’s longtime friend and competitor, advised the young novelist to cut out a full 2500 words from the opening sequence. This amounted to about thirty pages, with which Hemingway dutifully dispensed.

The result is striking. In media res, we’re led from a description of Robert Cohn, a mercurial, Jewish Princeton alum and boxing champ, to that of Jake Barnes, the book’s protagonist and Hemingway’s double. Barnes, like Hemingway, suffered a debilitating wound in WWI. The sad consequence of his wound is that he’s been reduced to a state of sexual impotence, a handicap than which, for a young man surrounded by beautiful, bibulous, uninhibited European women, there can be none worse.

One such woman is Brett Ashley, the wealthy, twice-divorced British socialite with whom Jake is in love. Sadly, his love is unrequited. Indeed, it’s unrequitable. For a multitude of reasons (not least among them the dysfunction of his generative part), Jake is unable fully to win her affection. Jake desires love, but is incapable of making love. And it is in the “making” that his beloved Brett is most interested. For Jake, a kind of reverse sublimation is needed–a movement from the high to the low, from the contemplative and the divine to the animal and the carnal. You could say that it’s Freud turned over on his head.

(As an aside, it may be of some significance that “Brett” is a man’s name, and that her sexual behavior–voracious, to put it mildly–is more identifiably male than female. This is one of the central themes of the book: an upheaval and revolution of old sexual mores. Brett, as the new, modern, liberated woman, can freely overleap the high Victorian walls by which her fore-sisters were hemmed in. She doesn’t hesitate to take that leap).

For Brett–the aristocratic femme fatale–it’s just the opposite; her appetite is purely sexual. She doesn’t want love. She doesn’t want a soulmate. Yikes!–least of all does she want another marriage! She twice tried the sacrament. It suited her ill.

She yearns, instead, for the immediate gratification of the flesh. She wants pleasure. After two divorces, she proceeds to have affairs with the aforementioned Robert Cohn, and the dashing young Spanish bullfighter, Romero. The latter is only nineteen years of age, a striking contrast to her ripened thirty four. No matter; equipped with her ageless charm, she is successful in seducing him (like Cleopatra, “age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety…”).

In this sense, the relationship between Jake and Brett is tragic: by the edict of fate, it will forever remain unconsummated. This tension drives much of the novel’s drama.

Brett is, in my opinion, a moral abomination. She’s really quite bad. And yet, like Shakespeare’s Cleopatra or Iago, she’s the most fascinating character in the play. Jake, frankly, lacks depth. He’s a one-dimensional man. Brett, on the other hand, is frustratingly complex. Her ladyhood is a labyrinth. She can, with the blink of an eye, elicit sympathy or antipathy. She can alternate between being totally heartless, to being almost childlike and lovable. She is, as I said, endowed with “infinite variety”. That variety is alluring, if not always commendable.

I want to take a moment and share a few excerpts from the book that I found particularly striking. I hope that you’ll agree:

“Don’t you ever get the feeling that all your life is going by and you’re not taking advantage of it? Do you realize you’ve lived nearly half the time you have to live already?”

Yes. Most piercingly, I do. In fact, it’s a thought that frequently keeps me awake at night.

“Women made such swell friends. Awfully swell. In the first place, you had to be in love with a woman to have a basis of friendship. I had been having Brett for a friend. I had not been thinking about her side of it. I had been getting something for nothing. That only delayed the presentation of the bill. The bill always came”.

Always.

Finally, I include this passage as an example of Hemingway’s spare, curt, “reporter” style, against which my own grandiloquent spirit cannot but bristle:

“I could not find the bathroom. After a while I found it. There was a deep stone tub. I turned on the taps and the water would not run. I sat down on the edge of the bath-tub. When I got up to go I found I had taken off my shoes. I hunted for them and found them and carried them down-stairs. I found my room and went inside and undressed and got into bed”.

Not even ChatGPT could produce something that mechanical! It verges on the robotic.

I suppose now is as good a time as any to mention Hemingway’s “Iceberg Theory”, a literary technique for which the author is famous. It was put to masterful use in The Sun Also Rises. Without giving you its definition, you can almost guess what it entails from the quotes I’ve provided above. It almost explains itself.

Imagine a giant iceberg, of which only the top one-eighth is visible. The bottom seven-eighths are concealed beneath the surface. You know not precisely how deeply they plunge. You know not where they end. It was to this extent that Hemingway liked to expose his plot: he gave you one-eighth. That’s all. As for the undisclosed other seven-eighths, it would be for you, brave reader, to guess at their dimensions.

Hemnigway was convinced that a writer can omit things that he alone knows about, so long as he writes truly. Yes, that was the important condition on which all else hinged: truth. Through an author’s truth, the reader will detect that which is omitted. Like a dog whose sense of smell is finely tuned, the reader will sniff it out. It can remain unspoken. The reader, then, becomes a kind of collaborator in the narrative process, and is all the more fulfilled by the development of a story in which he feels himself to be an active participant.

Of course, it’s not fulfilling for everyone.

Some prefer the laconic Hemingway approach. Some like to ponder the murky, fathomless depths to which the roots of the iceberg stretch. Others, like me, prefer the vista to be visibly drawn. We prefer the attic style of De Quincey or James. We are awed not by bashful icebergs bobbing on the surface, but by full, grand, picturesque mountain ranges that tower, in all their rocky grandeur, over the entire world.

Some like mountains, while others like icebergs. To each his aesthetic, geologic preference.

A FAREWELL TO ARMS

A Farewell To Arms is, in my opinion, Hemingway’s best novel. Published in 1929, it was promptly censored by the Italian authorities. The Fascists in power looked upon its depiction of Italy’s lukewarm effort in WWI disapprovingly. If you ask me, I think that they were being just a bit too sensitive; Hemingway’s portrayal of the Italian army isn’t totally unflattering and it isn’t an overtly political book. Nevertheless, it remained unobtainable in Italy until the fall of the fascist regime at the conclusion of WWII.

The title of the work is taken from that of a little-known poem, by an even lesser-known English poet, who lived in the sixteenth century: George Peele. Before finally settling on Peele’s title, Hemingway considered borrowing a line from The Jew of Malta, Christopher Marlowe’s anti-Semitic masterpiece: “In another country and besides”. It’s with this memorable response that an unrepentant Barabas answers Father Barnardine’s charge of fornication. A Farewell To Arms is a near-perfect title, but In Another Country And Besides would’ve done very well.

Like For Whom The Bell Tolls, A Farewell To Arms is a love story told against the backdrop of war. Or, better yet, it’s a war story told against the backdrop of love. One can’t be sure.

Lieutenant Frederic Henry, a close shadow of Hemingway, is a young American serving in the Italian army. Like Hemingway, he is an ambulance driver (Hemingway was deemed physically unfit to serve in the American army during WWI. To circumvent his debility (an issue with his eyesight), and to get a taste of some real action, he volunteered for the Red Cross. Through this organization, he was assigned to an Italian ambulance brigade. How his vision was good enough to operate a vehicle is anyone’s guess).

For all his faults, Henry proves himself to be a good soldier capable of noble deeds. Unlike Robert Jordan and Jake Barnes, he isn’t an intellectual (“I was not made to think. I was made to eat. My God, yes. Eat and drink and sleep with Catherine”). In keeping with the quasi-autobiographical tale, he sustains an injury that forces him away from the field of battle. When asked how he was injured (“Did you do any heroic act?”), Henry matter-of-factly replies, “No…I was blown up while we were eating cheese”. It just goes to show that not every act performed during a war is heroic, nor is every scene romantic. We can’t all be Robert Jordan sacrificing himself to blow up a bridge with his last breath.

During his period of convalescence, Henry falls in love with an English nurse by the name of Catherine Barkley. She’s based on Agnes Von Kurowsky, a young American nurse under whose care Hemingway fell when stationed in Milan. What begins as a lusty liaison ends up in an avowal to be wed. No sooner is a child conceived of their torrid affair than Henry is redeployed to the front. There, his unit suffers a terrible defeat, for which an act of treason is thought to be responsible. Facing execution by firing squad, Henry goes AWOL, scoops up Catherine, rents a boat, and flees to a safe harbor in nearby Switzerland.

Deep and high in the bucolic Swiss mountains, Henry and Catherine live a peaceful life. The day of her delivery arrives and, with it, her death. The final heart-stopping scene, of which Hemingway allegedly composed thirty-nine different versions, is one of the best in American literature. It is, in my opinion, a perfect ending.

What more can I say?

We must now hear from the author himself.

Here are a few of the most memorable excerpts from A Farewell To Arms:

“You understand but you do not love God”.

“No.”

“You do not love Him at all?” he asked.

“I am afraid of Him in the night sometimes.”

“You should love Him.”

“I don’t love much.”

“When you love you wish to do things for. You wish to sacrifice for. You wish to serve”.

Is this not the true meaning of Christian love?–to will the good of the other? As the plot progresses, as Henry becomes further detached from the war and more intimate with Catherine, he slowly learns how to love. He graduates, step by step, from a love of the flesh to a love of the soul. A love of God might not be so distant.

“Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments, and the dates”.

Abstractions become obscenities when brought before the real thing. They collapse before the concrete. For a poet, it’s easy to romanticize horror. Tennyson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade, I think, does the best job of balancing the two: the abstract splendor (When can their glory fade? Honor the charge they made!) and the concrete terror (Into the valley of Death rode the six hundred). Only a great writer can achieve this. Tennyson and Hemingway are among the few.

And, finally, this moving passage on one such abstract word–courage:

“If people bring so much courage to this world the world has to kill them to break them, so of course it kills them. The world breaks every one and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle, and the very brave impartially”.

Substitute the name, “Jesus” for the word “people”, and I think you’ll understand the real meaning of Hemingway’s statement.

One symbol to remark upon is rain, of which Catherine expresses her fear early in the novel:

“I’m afraid of the rain because sometimes I see me dead in it…and sometimes I see you dead in it”.

Prescient.

Rain, typically a symbol of cleansing and rebirth, is, in this instance, a symbol of death. On the night when Catherine gives birth, it is raining. Her prediction, then, is spot on: she dies in the rain. After all is said and done, it turns out that she had good cause to be fearful. Although Henry doesn’t technically join her by dying in the rain (as she admits to “sometimes” seeing him do) the image of Henry in the form of his stillborn child does. Henry, newly embodied in his lifeless child, dies. In this way, he too symbolically dies in the rain.

The foreshadowing is, I admit, a little bit thick, but it works. And the word on which the novel ends is–you guessed it!–rain.

Another symbol deserving of mention is sleep. Sleep and night. When asked what he believes in, Henry replies “In sleep”. That is his creed. That is his religion. He declares his allegiance neither to socialism nor to anarchism, but to sleep. To liberalism and authoritarianism, he’s indifferent. He is, however, a staunch advocate of sleep. He’s undecided about God and the afterlife, but he’s confirmed in his belief in bedtime.

Sleep is oblivion. Sleep is forgetting. It is a temporary state of nothingness into which we all unconsciously slip. In a broader sense, sleep is death. Death is the final, everlasting sleep to which our mortal selves will eventually yield. By saying that he believes in “sleep”, Henry is affirming that he believes in nothing. Is he a nihilist? In a way, he’s announcing his embrace of death. But, ultimately, he is not the one who dies. It is Catherine and his child who enter into a permanent sleep. Sad and alone, he is left awake.

SHORT STORIES

“Hemingway is one of the finest short story writers in the western tradition; he does not occupy that same eminence as a novelist”.

That’s the verdict given by the late Harold Bloom, from whose erudite judgment a layman like me wouldn’t dare dissent. Thus, as a layman, I’m obliged to agree; Bloom, I think, is correct. Hemingway, on a list of the top one hundred novelists in the western canon, probably ranks somewhere in the middle of the pack. No small feat, it should be said, for a midwest kid who forewent college and spent his days drinking, womanizing, and hunting big game.

As a writer of short stories, however, he ranks near the top.

My favorite works include The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber; The Snows of Kilimanjaro; The Battler; Soldier’s Home; Hills Like White Elephants; A Clean, Well-Lighted Place; and The Gambler, the Nun, and the Radio.

These half dozen short stories can be read in a single afternoon. Each is guaranteed to delight.

And with that, dear reader, I return my collection of Hemingway books to their lofty perch on my overstuffed shelf. Swept clean of their dust, freshly opened and loved, I can tell that they’ve thoroughly enjoyed the attention they’ve received. And I’ve certainly enjoyed the pleasure they’ve given me. And I hope that this little essay, my “reflection” on Hemingway, has given you some pleasure as well.

In closing, I leave you with the following quote:

“There is no friend as loyal as a book”.

Indeed, there isn’t. Hemingway knew this best of all.

And there is no book as loyal as one written by Papa. No–there is none quite as loyal, for there is none quite as true.